The annual renewal of the UN arms embargo on South Sudan is scheduled for a vote this May. In this interview, Crisis Group expert Maya Ungar warns that fully ending the embargo could fuel a return to civil war in the country.

What will happen?

Later this month, the UN Security Council will vote on whether to renew the arms embargo on South Sudan for another 12 months.

The vote comes as the country stands on the brink of a new civil war. Before the outbreak of fighting in March in Nasir, Upper Nile State, it seemed unlikely that the minimum nine votes needed to extend the embargo could be secured, as the South Sudanese government-arguing that sanctions impede its efforts to maintain security-had convinced an increasing number of Council members to end the embargo. However, the risk of a return to full-scale war, along with signals from the new U.S. administration supporting the embargo, has made the outcome uncertain.

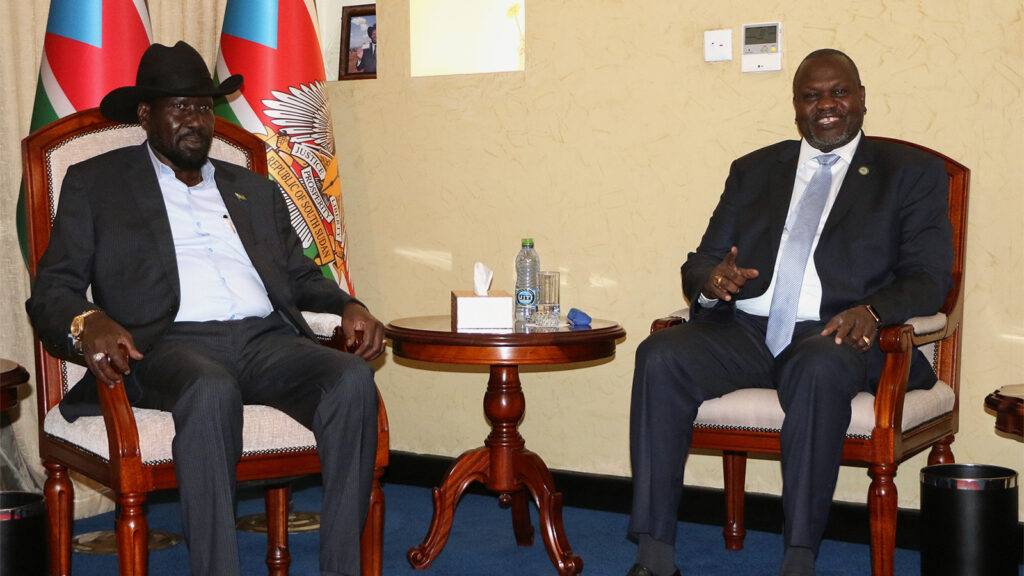

UN sanctions were first imposed on South Sudan in 2015, during the civil war that followed independence, between forces loyal to President Salva Kiir and those of Vice President Riek Machar, whom Kiir accused of attempting a coup in 2013.

The Security Council imposed asset freezes and travel bans on senior officers from both sides, but was slow to agree to a full arms embargo, partly due to opposition from China and Russia, who argued it could hinder peace efforts. In 2018, under President Donald Trump, the U.S. successfully pushed for a comprehensive embargo covering weapons, military vehicles, training, and other assistance, following repeated ceasefire violations. In 2022, the Council eased the embargo slightly, adding an exemption for non-lethal military equipment in support of the 2018 peace agreement, but the main elements remain in place.

Since the embargo was imposed, the South Sudanese government has lobbied for its removal, arguing it hinders the building of national security institutions and the training of the army. China and Russia support this position, though neither has vetoed the embargo’s renewal, as they do not see it as a core national security issue. South Sudan has also persuaded the Council’s three African members-who have previously objected to similar embargoes elsewhere-to oppose the measure. The U.S., European, Asian, and Latin American members have traditionally supported the embargo, arguing it is needed to prevent an influx of weapons and to pressure all parties to honor peace agreements.

Support for the embargo has eroded. In 2023, China, Russia, and the three African members abstained, reducing supporters to ten. In 2024, Guyana joined the abstainers, bringing the number to nine-the minimum required. Diplomats expect Pakistan, which replaced Japan, may vote to lift the embargo, potentially ending it. However, recent escalations may prompt some members to reconsider.

A recent UN Secretary-General’s report highlighted limited progress on security sector reform, with no significant advances in disarmament, reducing sexual violence, or securing arms stockpiles. The report noted that weapon-free zones in protection camps have reduced conflict-related sexual violence, but renewed fighting may reverse even these modest gains.

What should the Security Council do?

Despite its flaws, lifting the embargo now could escalate violence. Since fighting broke out in Nasir, President Kiir has cracked down on opponents, jailed Vice President Machar, rejected mediation, and blocked regional leaders from contacting Machar. Ending the embargo would likely be seen by the government as a green light to intensify its offensive with little international restraint, and by the opposition as a signal to prepare for more deadly conflict.

Even if the embargo is only partially effective, the Security Council should maintain it and increase pressure on all parties and regional actors to comply. The Council could remind member states of their obligation to enforce the embargo nationally, as the U.S. did in 2024 by arresting two South Sudanese opposition activists for attempting to export arms in violation of the embargo. The UN Panel of Experts has not recorded similar enforcement elsewhere.

Given the risk of escalating violence, the Council should pass a technical rollover of the embargo for one year. If negotiations stall, a compromise is preferable to lifting the embargo entirely. The Secretary-General’s report suggests exemptions for less-lethal equipment (such as tear gas for riot police) could address some government concerns.

The embargo should not remain indefinitely, but bold steps to lift it should only be considered if and when the current crisis subsides. Otherwise, Council members risk opening the arms market just as the country is on the verge of renewed civil war