When Mary Abdullah arrived at Bunj Hospital in the north of South Sudan eight days ago with her 13-month-old daughter, Jote, she feared the worst.

“When I brought her here, I was thinking … this girl will not survive,” she said.

Weighing just five kilograms, Jote was suffering from anemia and malnutrition, one of thousands of underweight babies in the East African country, where the United Nations estimates 2.3 million children are starving.

Abdullah, 30, typically feeds her family with the money she earns collecting firewood. Walking seven kilometres from her home across Maban County to reach the hospital meant losing days of income.

When she arrived, Abdullah found that since the reduction of some of the funding the hospital receives from the U.S. — administered through UNHCR, the UN refugee agency — in March, deliveries of medication had slowed and the number of nurses had been cut in half.

This meant there was no milk available for Jote that evening.

South Sudan holds the third-largest oil reserves in sub-Saharan Africa, and its government depends almost entirely on oil exports to stay afloat. But years of corruption, a five-year civil war, the conflict next door in Sudan — the route for those exports — and repeated weather events that have displaced thousands have left most people in South Sudan dependent on aid.

As of 2024, nine million people, or more than 70 per cent of the population, were dependent on some form of foreign assistance, according to the UN. Now, that dependence is colliding with shrinking resources and a hunger crisis.

The UN estimates 7.7 million people are facing food insecurity this year. This comes just as the U.S., which according to the Center for Global Development provides about 40 per cent of the country’s aid, has announced a major scaling back of foreign aid.

In January, President Donald Trump halted the majority of U.S. foreign aid. More than 80 per cent of USAID’s programs worldwide were cancelled by March and the agency shut its doors in July. Analysts say these funding cuts could lead to millions of deaths from illnesses like malnutrition, tuberculosis and malaria in the coming years.

Unpaid staff

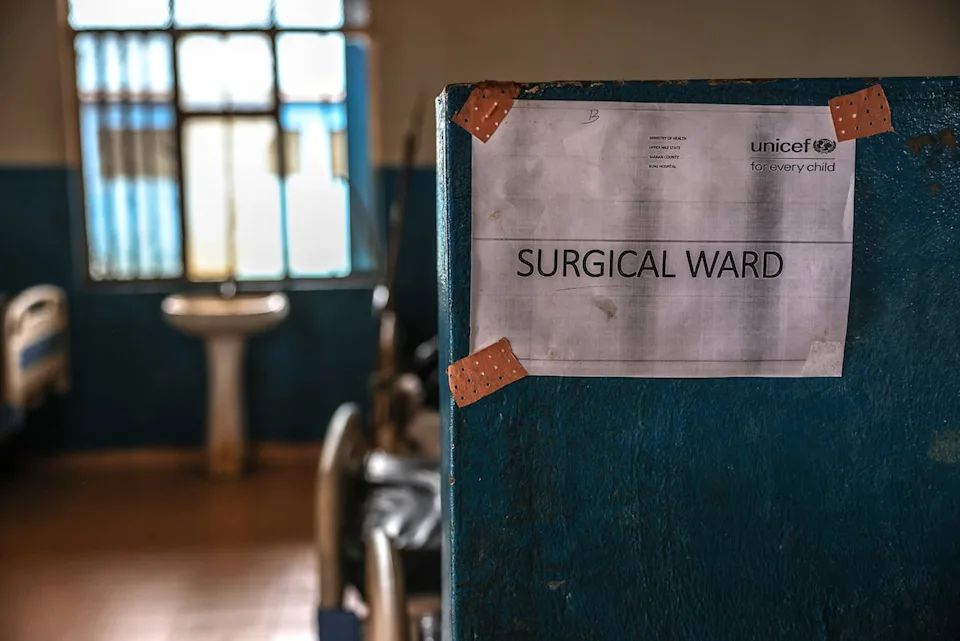

The pressure is visible at Bunj Hospital, the main facility for Maban County, less than 20 kilometres from the Sudanese border. Midwife Awatif Dawa says some essential medicines and equipment that once arrived monthly — such as sterile equipment used in blood transfusions — are now running out.

“I’m so worried because these are very important medications, and it’s lifesaving,” she said.

When CBC visited in late August, nurses, doctors, cleaners and administrative staff were on strike, leaving already dirty and bare wards unattended. They hadn’t been paid in six months, said nurse Jacob Zachariah Kamis.

“My children at home are very hungry,” he said. His salary supports not only his nine children but other relatives, too.

In cities like Juba, Bor and Maban, health-care and humanitarian workers told CBC News they were supporting as many as 50 family members with their salary. Countrywide, foreign aid accounts for roughly a quarter of gross national income.

Kamis says he is torn between duty to his patients and an obligation to his family.

“I’m a nurse. I work to save the life of people…. if I leave my work, the people in the hospital will be suffering. So, it will not be easy,” he said.

Canadian Danny Glenwright of Save the Children says the group has lost nearly a third of its South Sudan budget due to U.S. aid cuts.

“Our sector is reeling right now from massive cuts, and yet the needs have increased dramatically — because of the protracted crisis, climate change and the rising cost of living,” he said.

Aid cuts amid other challenges

For local NGOs, the blow has been devastating.

Gloria Soma, executive director of the TiTi Foundation, said nearly half of South Sudan’s national aid organizations have had to close since March. She said her group — which focuses on job opportunities, education and food security — lost $3.5 million in UNICEF-channelled funds that disappeared when the U.S. pulled its support.

“It takes so long and so many years of hard work to prove yourself worthy of that fund as a local actor. Then suddenly, you are told, ‘It’s over,'” Soma said. “It’s quite frustrating.”

Much of that money was meant to support the influx of refugees from Sudan, where war has displaced millions of people since 2023. South Sudan now hosts more than 500,000 refugees and asylum seekers, mostly Sudanese, alongside more than two million internally displaced people of its own. This year the UN refugee agency has lost 30 per cent of its funding in South Sudan as a result of USAID cuts.

“The influx was high and the needs were extreme,” Soma said. “We are already having our own challenges as a nation. This fund was [meant] to lessen that burden a bit.

“Whoever is making all these decisions is miles away and is not seeing the impact on the ground.”

Cutbacks to foreign aid have come as the country is suffering an economic crisis, climate shocks like flooding and a resurgence of ethnic violence.

‘This year is the worst ever’

In Doro refugee camp, near the northern border with Sudan, Aisha Ajab scrapes together a living by cooking and washing dishes at the reception centre, through which thousands of Sudanese have passed since the outbreak of the neighbouring civil war in 2023. Her pay no longer covers the cost of food for her family.

“This year is the worst ever,” she said.

According to the African Development Bank, 92 per cent of South Sudan’s population now lives below the poverty line, a 12 per cent increase over last year.

“Because of the rainy season…. we cultivated, but the seeds did not germinate,” Ajab said.

South Sudan is one of the countries most vulnerable to extreme weather events like flooding. An especially heavy rainy season this year has hampered agricultural production, as the UN expects more than 400,000 people to be displaced by “deadly” flooding by the end of the year. The country is also battling its worst cholera outbreak in decades, which has already taken more than 1,400 lives this year.

What’s more, the country remains politically unstable seven years after the end of a civil war that killed more than 400,000 people. A fragile peace agreement has hampered efforts to establish a stable government and robust civil society and led to a volatile security situation.

A recent resurgence of fighting in the north of the country cut off key aid supply routes and forced 165,000 from their homes, pushing more people into hunger and need.

‘Policy failures’

Humanitarian workers say the reliance on aid combined with shrinking financial support has postponed hope of greater stability and security, which would allow the country to be less dependent on foreign donors.

“We were always supposed to be replaced,” said Jason Matus, a development consultant who has spent his 30-year career working with South Sudan, of the foreign NGOs that provide so many of the services South Sudanese rely on.

He said the aid sector was meant to be replaced “by a government that’s accountable and responsive to its people, by a private sector that is ethical, by a society that is cohesive and empathetic and by a physical environment that is capable of managing the demands on it for people to survive.”

This past week, UN investigators accused South Sudan’s authorities of siphoning off billions of dollars in public funds since independence in 2011. In a report released Tuesday, the UN Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan said officials allegedly employed multiple schemes to divert large sums from state revenues over the past decade.

“The [aid] sector hasn’t failed because there are no humanitarian solutions to humanitarian problems. These are policy failures,” said Danny Glennwright.

“Everything costs more money to do, and we have less money than ever to do it.”

Source: CBC